The Pain Assessment

It’s Not Just a Number!

Having your pain assessed well is one of the most important steps in achieving quality pain care. Documenting critical information allows your health care provider(s) to better understand YOUR pain experience and build a pain care plan with YOU that works for YOU.

In 1992, the Federal Agency for Health Research and Quality stated, “the most reliable indicator of pain comes from the self-report.” Research shows that health care providers – even pain experts – do not accurately interpret the degree of pain that patients are experiencing. To better understand pain, the person with pain and the health care provider must have a thoughtful and targeted conversation. TOGETHER, providers and individuals must be willing and able to work as a team – your pain care team.

Tips for the Person with Pain

Your Health Care Appointment

(Cohen Tips from The Empowered Patient)

As a person living with pain, your job is to work with your pain care provider and “Get it DUN”:

- Get a specific Diagnosis

- Understand Your Treatment Plan

- Find out the Next Steps

Office Visit Checklist:

- Be prepared and do your homework; be ready to cover your top 3 priorities. Remember that the average visit lasts 8 minutes, with the first interruption in your conversation occurs within 23 seconds. If you have a long list of issues or spend your time telling the long version or your story, you will lose ground quickly.

- Bring your list. Have on hand and offer your list of key questions, a list of your current medications with how many you have left or bring them with you, a brief summary of your medical condition(s) and your current pain treatment plan.

- Have on hand a copy of important documents (especially for the first visit). Share your copy of your medical records (be sure to get them back before you leave), any medical tests done within the past year (blood tests, X-rays, CT scans, MRI’s, etc.)

- Bring your “Get it DUN” cheat sheet. Use this to prompt your questions and request for clarification when needed. Use your pain diary or see page 184 in the appendix of “The Empowered Patient”.

- Learn how to get an appointment in a timely fashion. When told by the front office that your provider has a long wait list for your next appointment, ask to speak to the office nurse, manager or physician directly.

- Avoid long waits in the waiting room. Schedule your appointment in the beginning of office hours or right after lunch. If your provider treats children—avoid school holidays, early in the summer vacation period and right before the school year begins.

- Slow down your rushed provider. Calmly and politely make comments like, “Having a busy day? (or) “May I take a few minutes to ask some questions?

- Ask for your provider’s email address. Promise to use is respectfully and not excessively—reserve its use for problems or need for clarification. If given to you—keep your promise. If this is denied, you may consider this a deal breaker and decide to find a new provider who is willing to be more accessible.

- Take your “pain buddy” or an advocate with you. This person can help take notes of the answers to your questions, prompt you to stay focused on your top priorities and serve as your memory by reviewing what was explained once the visit is over. He/she can be a valued, trusted member of your team by helping you work on your pain care plan in between office visits.

- Treat this visit as if you are paying over $500 for this visit. This will force you to make the most of your time so you get your money’s worth.

If you leave the appointment, saying “Huh?”— You are already behind the eight ball. Call back and ask to speak to your provider for clarity or email your questions. Don’t have their email address? Here are some alternative ways to obtain it:

- Perform an online search (Google, Bing, etc.) for their contact information; look to see if any publications, journal articles or presentations are available—the email may be included.

- If the provider works at a medical center or university, search in their medical directory

- If missing, look how that institution lists their email address and try a best guess try using their format by inserting your provider’s name (ex. jane.doe@universityhealth.org)

Source (with minor modifications) : Cohen, E.S., The Empowered Patient: Getting the Right Diagnosis, Buy the Cheapest Drugs, Beat your Insurance Company and Get the Best Medical Care Every Time, Ballentine Books, New York, NY: 2010. Accessed online on Feb 26, 2013: http://www.amazon.com/Empowered-Patient-Diagnosis-Cheapest-Insurance/dp/0345513746.

Tips for the Health Care Provider

A successful pain interview

(excerpt from 2010 ASPMN Core Curriculum, Chapter 13)

- Create environment of courtesy, interest and desire to help

- Greet while being alert to individual’s comfort; need to reposition, etc.

- Use open ended question: Can you share with me about…?

- Follow your patient’s lead:

- Facilitate by posture, eye contact, voice tone

- Reflection by repetition of message heard

- Clarify by coaching; ask for more information as needed

- Empathetic responses during interpretation

- Confront gently when feelings of anger, anxiety, depression or fear are expressed or suspected.

Assessment Tools: Providers use many different clinical tools used that have been well researched and have proven value over time. Some form of a pain assessment should be used in every practice setting. Whichever pain assessment tool your health care provider uses, it should contain come key elements. They are:

- The self-report that pain exists. A simple question like: Are you in pain? (Yes or No)

- If yes, the assessment continues.

- Location: Commonly an outline of a human figure, back and front is provided where you can indicate where you feel your pain. You may be asked to place a simple mark, arrows, or shade areas on one or more locations. Some may recommend that you prioritize the area(s) that cause you the most concern (#1 is my worse or more challenging area, for example).

- Description: What does the pain sensation feel like? There may be words to circle or an area where you can use your own words. The description helps your health care provider to select what may be the underlying cause of the pain. Examples are:

- Sharp; Dull

- Stabbing; Throbbing

- Squeezing; Colicky

- Burning; Shooting

- Heavy; Pressure

There may be a section where you are asked to describe your pain in your own words.

- “It feels like 2 dogs are fighting inside my belly”

- “My feet are numb and they feel like they are on fire at the same time”

- “An elephant is sitting on my chest”

- “My head has a vice around it from the back of my neck to over my forehead”

- “An ice pick is stabbing my left eye”

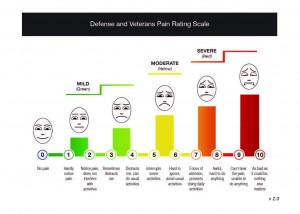

- Intensity: This is where the pain scoring is used – the zero (no pain) to 10 (worse imaginable pain) pain scale is most commonly used. New tools have been developed and tested that help explain the effect of that pain on your ability to function. Colors and faces have been included. The newest tool modified for the military and veteran population has undergone rigorous testing.

Pain intensity should be measured during several times – for example, when you are at rest, when you are moving, what you are experiencing now and perhaps the worst pain you had over the past few days. Pain intensity scores can be used to measure effectiveness of comfort measures, as well. For example, when you get up in the morning and are stiff, rate your pain; then stretch, take a warm shower and rate it again.

Some people with pain have voiced their concerns about how pain scales are used during office visits and hospital stays. Many blame the use of the pain score, but digging deeper, the primary complaint seems to focus on how someone is approached with the question “what is your pain score?” An abrupt tone of voice and the failure to ask follow-up questions to seek understanding are far too common. Health care providers must be mindful that pain intensity scores are just one small piece to the pain puzzle and should never be considered the full pain assessment.

There are a variety of pain rating tools that can be used depending on the needs of the person being evaluated:

- Infant and children

- Elders

- Various languages

- Multi-dimensional tools that also measure mood, sleep, appetite, self-care, etc.

- Those who have difficulty thinking or understanding

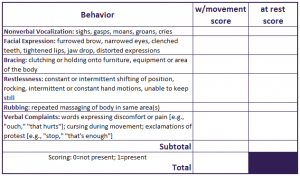

- Those who are unable to self-report; one example is the Checklist for Non-verbal Pain Indicators (CNPI)

- Timing: When does the pain occur? Does it come and go? If so, are their activities or events that cause it? Is it always there? If so, does it stay the same? Does the time of day or change in the weather affect it? Keeping a pain diary, journal or notebook will help you answer these questions. There are smartphone apps now available.

- Effect of pain treatment measures: What makes the pain ease or flare up? What have you tried to lessen the pain or help you continue through your day? List any comfort measures such as ice, heat, exercise, stretching, rest breaks, braces, dietary changes or supplements, over the counter medications, prescription medications, special injections, surgery, acupuncture, chiropractic manipulations, etc. What worked and what did not? Did you experience any side effects from the pain treatment measures? If so, what were they?